Last year it only took us an extra 72 days to earn the same as our male colleagues.[1]

To be clear, when we say “we”, we don’t mean “Betricia” and “Sidsel”, and when we say “our male colleagues”, we don’t mean the men who are employed at Sign In Workspace.

No.

So if we’re not talking about us and our immediate colleagues, what are we talking about?

We’re talking about, the fact that women’s full-time earnings make up 83.1 percent of what men earn, and women’s part time earnings make up 77.3 percent of men’s.[2]

We’re talking about the fact that women are 14% less likely to be promoted than men.[3]

And we’re talking about the fact that today is the day women as a whole catch up to men’s earning throughout 2022.

And we’re 72 days into 2023.

It’s women’s history month, and last year Malene Platt and Kasper Ullits wrote an excellent article about women in the workplace on this site, but this year we wanted to narrow it down a little bit.

You see, while women as a whole catch up to men’s earnings on March 14, we (Sidsel and Betricia) still have a way to go before we catch up.

The thing is, we’re not just women, we’re mothers too.

And our Equal Pay Day is still 154 days away.[1]

What is Equal Pay Day?

Equal Pay Day is the day on which women’s earnings catch up to that of what men’s average earnings the previous year.

Or said in a different way, from January 1, 2022, to March 14, 2023, women earned the same amount on average, as men did from January 1, 2022 to January 1, 2023.

But this is based on women as a whole.

In reality, there are several Equal Pay Days throughout the year. There is one for black women, one for Latinas, one for Native-American women, and one for moms.

Equal Pay days in 2023

-

Equal Pay Day – for all women – is March 14.

-

Black Women’s Equal Pay Day is July 27. Black women are paid 74% and 64% of every dollar paid to white men.

-

Mom’s Equal Pay Day is August 15. Moms are paid 74% and 62% of every dollar paid to fathers.

-

Latina’s Equal Pay Day is October 5. Latinas are paid 57% and 54% of every dollar paid to white men.

-

Native Women’s Equal Pay Day is November 30. Native American women are paid 57% and 51% of every dollar paid to white men.

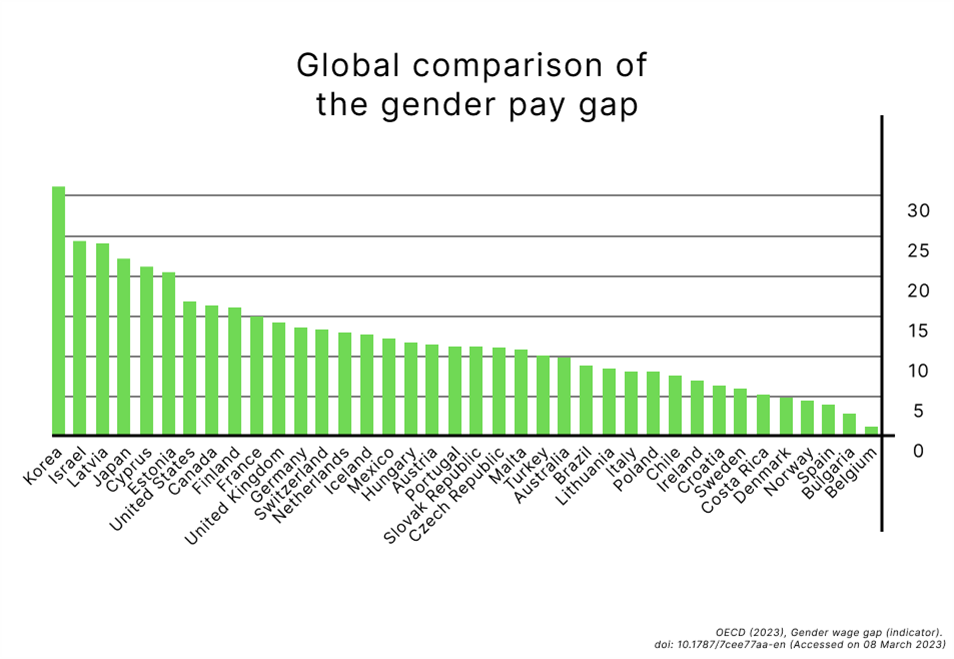

Gender wage gaps are a global issue

While the gap between men’s and women’s earnings has narrowed over the past years, it’s still a global issue in both developing and advanced countries. Especially considering the fact that the average gender wage gaps in both the European Union and the OECD are still above 10 percent.[8]

Why are mothers less likely to be promoted than fathers?

While working moms as a concept did become more widespread over the course of the 20th century it’s not a new thing – even from a historical perspective. In fact, 7.5 percent of mothers worked during Lincoln’s Presidency.[4]

But historical facts aside, there’s still a difference in opportunities for working mothers when compared to fathers.

In fact, according to the report ‘Employment Pathways and Occupational Change after Childbirth’ published by the universities of Bristol and Essex mothers were two thirds less likely to be promoted within the first five years of parenthood when compared to fathers.[3]

So, why is that?

To answer this question in full would take us more time than we have here, but a big part of the answer is that motherhood (and the associated gender differences in household care responsibilities) are significant factors when it comes to both the gender pay gap and what we could call the parental promotional paradigm.[5]

In fact, there’s a negative relationship between a woman’s wage and the number of children she has. According to data from OECD the ‘motherhood penalty’ amounts to a 7% wage reduction per child.[6]

In short, mothers are more likely to leave early to pick up their children, they are less likely to be able to make meetings late in the day, and they are more likely to arrive later in the morning because they need to drop off their children before they go to work.

While these things probably won’t affect productivity (lets be real, most moms work into the night to catch up on anything they didn’t get around to during the day), but it does affect how our managers see us.

If they see us leaving early, arriving late, or taking a day off to tend to a sick child, they’ll likely think of it as us being less invested in our jobs – as us being less productive.

And this in turn leads to fewer promotions and lower pay.

But there’s a balance coming.

Does hybrid work make it easier to be a working mom?

Yes, we’re going to talk about it.

We have to.

Because it’s levelling the playing field.

And it’s hybrid work.

You might be tired of hearing people tout the flexibility that comes with hybrid work as the ultimate benefit, but if you’re a woman you should be excited about it for other reasons than getting to work in your pajamas.

When your male colleagues don’t come to the office every day, or when they start to work at different times to suit their calendars, the responsibilities related to motherhood (drop off, pick up, sick days etc.) become less of an anomaly.

And as a benefit specifically tailored for us, working from home will often let us work more and pick up earlier, because we tend to choose day-care options located close to home and not close to our offices.

Full steam ahead

In 2018 the Global Gender Gap Report concluded that based on the current rate it would take 202 years to close the gender pay gap.[7]

But in 2018 everyone was still going to the office five days a week too.

And we aren’t doing that anymore.

In 2023 we’re flexible, we’re remote, and as a society we’re more focused on gender equality now than we were five years ago.

Of course, we need to keep talking about gender gaps in the workplace. We need to keep focusing on how to increase equality from year to year. But for now, we allow ourselves to be at least a little hopeful that the future will be more equal than the past.

References

[1] https://www.aauw.org/resources/article/equal-pay-day-calendar/

[2] https://iwpr.org/iwpr-publications/fact-sheet/gender-wage-gaps-remain-wide-in-year-two-of-the-pandemic/

[3] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gender-equality-at-work-research-on-the-barriers-to-womens-progression

[4] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/parenting/wp/2014/05/08/the-history-of-mothers-and-working/

[5] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/03/an-economist-explains-why-women-get-paid-less/

[6] https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/lackofsupportformotherhoodhurtingwomenscareerprospectsdespitegainsineducationandemploymentsaysoecd.html

[7] https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2018

[8] OECD (2023), Gender wage gap (indicator). doi: 10.1787/7cee77aa-en (Accessed on 08 March 2023)